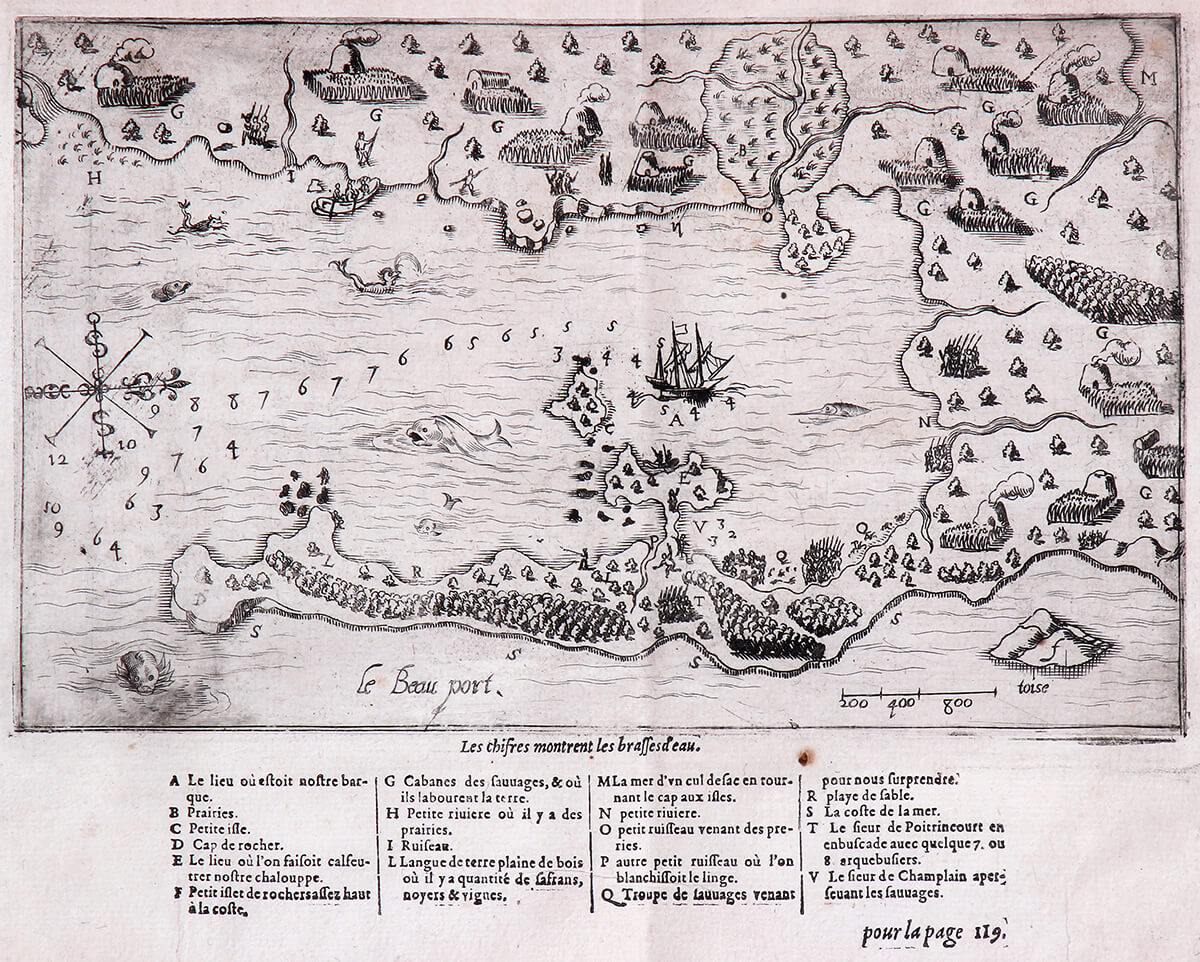

Samuel de Champlain (ca. 1567–1635), le Beau port, map drawn for Les Voyages. Originally printed in Paris, 1613. Cape Ann Museum. Gift of Tamara Greeman, 2011 [acc. #2011.34]

The Cape Ann Museum celebrates Cape Ann as a place, and an important part of its legacy is our area's Native American history. This edition of CAM Connects provides a preliminary insight into Indigenous peoples of Cape Ann as part of the Museum’s desire to strengthen an understanding of this story. Moving ahead we look forward to partnering with organizations, scholars, and descendants of the Cape Ann Native American population to ensure that this significant narrative is appropriately documented and shared broadly with our audiences. ■

Native Americans of Cape Ann

The map from "Les Voyages" in the Cape Ann Gallery is an especially noteworthy document in CAM's historical collection. Drawn from the explorations of Samuel de Champlain in 1604 and 1606, it is one of the earliest renderings of Gloucester harbor, "le Beau port."

The Champlain map illustrates recognizable features of the local landscape, such as Rocky Neck, Eastern Point and Ten Pound Island. On closer examination, it also reveals something else quite significant - the extent of Native American settlements along our shores. The map depicts dwellings, planted crops and managed woodlots. Who were these Indigenous people, and what kind of lives did they lead? Much of their story has been lost to history, but recent scholarship by local historians such as Mary Ellen Lepionka, along with the collection of artifacts and archival documents at the Museum, is helping uncover a fuller picture of this thriving community.

At the time of the Champlain encounters, the native people were the Pawtucket, part of the Algonquian-speaking confederacies of the Northeast. The Pawtucket were recent migrants into Essex County and were descendants of Algonquian-speaking people who lived in New England from around 3,000 years ago. Evidence of their presence can be found throughout Cape Ann. Ancient shell piles or "middens" on the shores of the Essex River and the Annisquam River mark the sites of summer encampments visited over centuries. The Pawtucket had a village in Riverview, Gloucester, and a surviving rock formation on Pole's Hill served as a solar observatory, with boulders aligned to mark astronomical events such as the summer and winter solstices. The Museum's collection of pottery sherds, arrowheads, fishhooks, woodworking tools, and agricultural tools provide a glimpse of everyday life.

The language and customs of the Pawtucket were little understood by Champlain and his men, leading to misunderstanding and potential conflict. In a fascinating detail, the Champlain map portrays an example of one such misunderstanding, a presumed "ambush" by the Pawtucket on Champlain’s party at Rocky Neck. A close look shows the French raising the alarm while the Pawtucket dance in a circle on the beach at Smith’s Cove. (According to Champlain’s account, he is one of the men shown, along with his second in command Poitrincourt and the captain of his marines, raising the alarm).

By the early 17th century, the Pawtucket were living alongside English settlers. Fearing raids by the Tarrantines, enemies from the North, the Pawtucket welcomed the protection of the new settlers (the “Tarrantines” were the Micmac, Passamoquoddy, Maliseet, and sometimes Penobscot). Masconomet, the hereditary leader or "sagamore," sold his farm in Ipswich and other Pawtucket homelands to John Winthrop, Jr. Masconomet had earlier (in 1629) rented cropland on Cape Ann to John Endicott, governor of the New England Company at Beverly-Salem.

Over time, native populations in coastal New England were ravaged by European diseases and greatly diminished in number. During the 1670s, the tranquil coexistence of the Pawtucket and the English came to an end following a disastrous Wampanoag war against the English in which the Pawtucket had tried to remain neutral. The native people in Essex County fled to northern New Hampshire and Vermont or to Canada, or were confined to reservations on the frontiers, or were forced into involuntary servitude in the towns. Gradually, their history, the memory of them, and their role in shaping the American nation were largely erased.

The Cape Ann Museum presents and celebrates the people, history, art and culture of this special region. As the Museum prepares for its 150th anniversary, and Gloucester its 400th anniversary of the first European settlement on Cape Ann, the story of our area’s Indigenous people needs to be further explored and told anew. With its collection, programs and scholarship, the Museum is well poised to play a role in this important initiative. ■

Please visit our online exhibit, Unfolding Histories, for more on this history.

Carleton Phillips & Artifacts in CAM’s Collection

N. Carleton Phillips (1879-1952) was president

and general manager of the Russia Cement Company (makers of LePage’s Glue) in

West Gloucester for 25 years. He was

also an amateur archaeologist, and Native American artifacts that he collected

around Cape Ann from the early 1890s through the 1940s are now part of the

Museum’s holdings. Although Phillips was

not a trained archaeologist and while many of his collecting methods do not

meet modern standards, he did succeed in amassing an impressive array of

artifacts. Today, the collection (along

with transcripts of lectures Phillips gave on the subject of Native Americans

on Cape Ann) gives historians a trove of materials to work with as research

into this important subject continues.

David S. Crowley, Pole’s Hill, 1997. Watercolor on paper. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Gift of Kevin Jordan, 2000 [acc. #2000.49.02].

One of the many sites Phillips explored and collected artifacts from in Gloucester was Riverview, a neighborhood that includes Pole’s Hill, with its aforementioned solar observatory. Evidence, including artifacts collected by Phillips, tells us that there was a Pawtucket village just north of Pole’s Hill and that it was likely occupied by Native Americans for a long period of time, Indigenous peoples who would have climbed the precipice to observe the sky.

In 1998, citizens of Gloucester joined together to purchase Pole’s Hill and surrounding lands to save it from residential development. The site is now owned by the City of Gloucester.

Native American Artifacts. Collected around Cape Ann and donated to the Cape Ann Museum by N. Carleton Phillips. [acc. #2004-33-34-35].

In 1940, Carleton Phillips approached the Museum, then known as the “Cape Ann Scientific, Literary and Historical Association,” about gifting his collection of Native American relics to the organization. It would be more than a decade before the gift was made. Over the years, the Museum has made the collection accessible to researchers, used it to engage and educate school age children, and displayed a small segment of it in its Cape Ann Gallery. ■

Sculpture of "Masconomo"

The word “Masconomo” is familiar to many on Cape Ann as the name of a waterfront park and tree-shaded street in Manchester-by-the-Sea and has been referenced as the name of the first Native American to greet the Arabella when it arrived offshore south of present-day Manchester Harbor in 1630. However, hidden in plain sight in the foyer of Manchester Town Hall sits one of the more fitting tributes to this important figure from the town’s past, a bronze sculpture of Masconomo by twentieth century artist George Aarons.

George Aarons (1896-1980) was born in Lithuania and immigrated to the United States with his family when he was young. He attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and regularly visited Cape Ann in the 1940s, finally moving here year-round in the 1950s. During the 1930s, he began working under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) creating sculpture for public installations. In 1938, the WPA proposal from the town of Manchester-by-the-Sea called for the creation of a life-size statue to commemorate “Chief Masconomo” that would be placed in Masconomo Park.

Throughout Aarons’ career, his style would evolve from realistic to an increasingly abstract approach. Many of his works focused on the human form, and he maintained an interest throughout his life in conceptualizing the universality and humanity of struggling to thrive with dignity in a world that could often be cruel. Maybe it is no surprise then that when Aarons was awarded the commission for a sculpture to commemorate Masconomo, he created an image about as far from the then-popular trend of depicting Native Americans as grinning figures in feather headdresses and fringed leather garb as could possibly be imagined.

When he submitted his prototype for approval in 1938, Manchester town officials rejected his sculpture because it lacked just those characteristics that today we know are a false representation of Native American appearance in the 1600s. In the early 1980s, a group of Manchester townspeople learned about the errant project and purchased the plaster model from Aarons’ widow. Unable to afford the cost of casting a life-sized bronze, the group succeeded in having a statue the same size as the model cast and installed on the first floor of their Town Hall, while the original plaster model is currently on display at the Manchester Historical Museum.

George Aarons (1896-1980), Chief Masconomo. Plaster. Collection of the Manchester Historical Museum [acc. #85.28.1].

George Aarons (1896-1980), Chief Masconomo. Bronze. Manchester Town Hall.

The first image shows the original plaster cast by Aarons, held by the Manchester Historical Museum. The second shows the bronze sculpture as it looks today at the Manchester Town Hall.

So, the next time you are in Town Hall paying your taxes or a parking ticket, take a moment and pause at the unassuming bronze sculpture that stands just to the left of the Treasurer’s window. Notice the simple dignity of the squared shoulders and lifted chin, the quiet wisdom of the folded arms and closed eyes, the strength and vulnerability of the bare upper body, and the solidity of the columnar form anchored to the earth.

Today, no one knows for certain what Masconomo looked like. What he thought about the folks that arrived in the Arabella and the events that transpired over the ensuing years as the land he had relied upon for sustenance was gradually bargained away from him until he died in poverty in 1658 is an ongoing investigation. But there is a chance that the artistic vision of George Aarons has captured the collective courage that would be required to face a future that would prove to be increasingly uncertain and uncontrollable. ■

Read more about the life and work of George Aarons.

A special thank you to the Manchester Historical Museum for sharing their resources on George Aarons’ sculpture “Masconomo.” View more information about this piece and on the history of Manchester-by-the Sea.

Unsubscribe | Forward | View in browser

CAPE ANN MUSEUM

27 Pleasant Street, Gloucester, MA 01930

CAPE ANN MUSEUM GREEN

13 Poplar Street, Gloucester, MA 01930

Cape Ann is one of the most important places in the history of American art and industry.

The Cape Ann Museum, thanks to supporters like you, celebrates the history and remarkable contributions of this place to the cultural enhancement of our community and the world at large - yesterday, today and tomorro