Stephen Parrish (1846-1938), Rocky Neck, c.1880s. Etched copper plate. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Gift of Harold and Betty Bell, 1984 [acc. # 2451.04].

Printmaking

Printmaking is a broad term that encompasses a wide range of techniques and terminology, and while many printmaking disciplines can be classified as either relief, intaglio or planographic, some techniques blur the lines between these classifications or differ from them entirely. This week in CAM Connects, we’ll be taking a look at these three printmaking categories through the lens of the Museum’s collection and demystifying some of the processes along the way. ■

Relief Printing

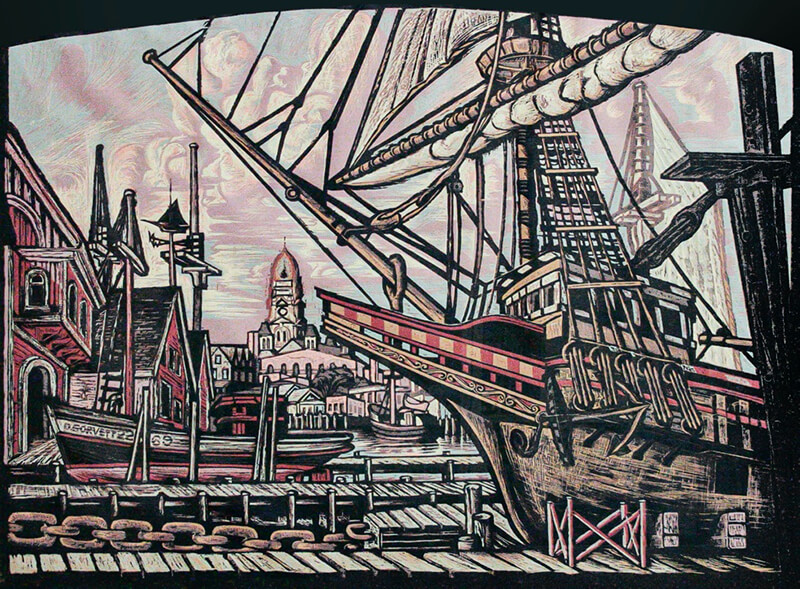

Don Gorvett, The Galleon Mayflower II in Dry Dock, 1996. Reduction woodcut print. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Museum purchase, 2017, funds generously provided by Arthur N. Ryan [acc. # 2017.8.1].

Relief printing is among the oldest and simplest forms of printmaking and is commonly done by applying ink to a carved block and pressing it onto a substrate (usually paper or cloth) to transfer the ink. Areas which have been cut away do not stand out in relief, therefore they don’t receive or transfer any ink. Blocks can be made from wood (resulting in a “woodcut”), linoleum (a “linocut”), or a host of other materials such as rubber or plastic. If a block is carved and printed over multiple intervals it is called a reduction print, so named for the way the block is physically reduced over the course of the process.

Video still from CAM Video Vault VL19 – Conversations with Contemporary Artists: Don Gorvett, Printmaker, 4/25/2009. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. .

For a more detailed look into this form of printmaking, watch this conversation with contemporary artist Don Gorvett. And to learn more about how Gorvett’s work has been influenced by his time on Cape Ann, head to this page on the Museum website that highlights the past exhibition Vincent, Weaver, Gorvett: Gloucester, Three Visions. ■

Printers

Extraordinaire – The Folly Cove Designers

No conversation about relief printing and Cape Ann would be complete without mentioning one of our most well-known and important groups of printmakers: The Folly Cove Designers.

Always a visitor favorite, the Cape Ann Museum’s Folly Cove Designer Gallery showcases the work of some of Cape Ann’s most talented printers, the women (and a few men!) who worked together for 30 years under the mantle of the Folly Cove Designers. The group was led by Virginia Lee Demetrios and specialized in relief printing: creating designs, cutting them into linoleum blocks and printing them with ink on linen. The fabric was made into placemats and napkins, clothing, curtains and other household items. Working from 1938 to 1969, the Designers achieved remarkable success, having some of their designs placed with such well known retailers as Lord & Taylor. Through their extraordinary attention to detail and artistic skills, the group inspired an ever-growing and enthusiastic group of admirers.

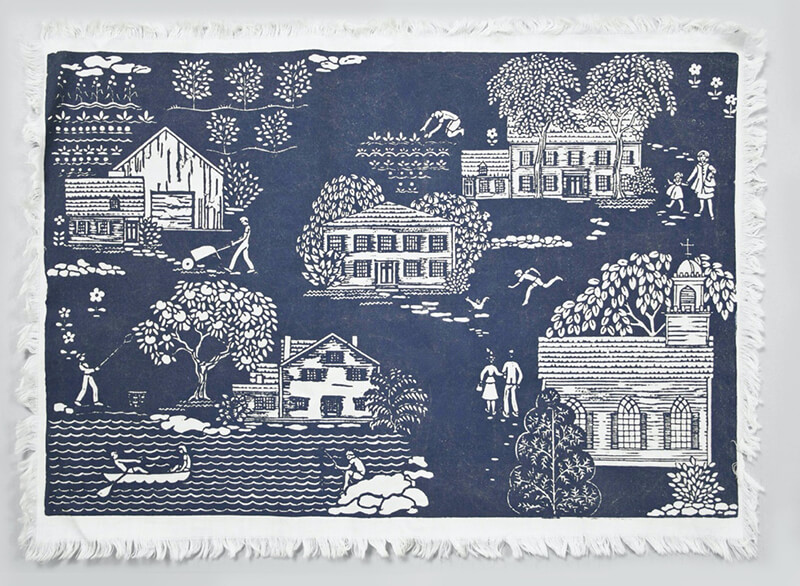

Louise T. Kenyon (1906-2000), Head of the Cove, c. 1945. Ink on linen. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Gift of Mary Wheeler, 2012 [acc. # 2012.104.7].

One of the most talented and prolific members of the Folly Cove Designers was Louise Tomlinson Kenyon (1906-1998). Louise joined the group in 1940 and over the next quarter of a century created and cut designs for 30 linoleum blocks. Many of them were used to make placemats and Louise’s sister, Grace Tomlinson Murray, spent hundreds of hours fringing the edges of the linen mats before they were printed on, as is seen in the above print. Like her sister, Grace Murray was a woman of many talents and in 2017, the Museum exhibited a remarkable collection of Andean-style knitted hats that she made. The hats were inspired by the work of indigenous knitters in Peru and Bolivia and today are the prized possession of families across Cape Ann. The Museum notes with sadness, that Grace Tomlinson Murray recently passed away. ■

Learn more about Louise Tomlinson Kenyon and the Folly Cove Designers

And to hear from CAM’s Curator, Martha Oaks, as she speaks about the Folly Cove Designers within the historical context of Cape Ann’s artistic tradition, view this 2015 interview conducted by Christine Lundberg and Rawn Fulton.

Intaglio Printing

Like relief, the intaglio process involves the physical manipulation of a flat plane in the form of a plate. In this case, instead of carving away broad areas, intaglio printers scratch thin lines using a sharp spike-like hand tool called a burin. This can be done directly into the bare plate (resulting in a “drypoint”) or after the plate has been coated with an acid-resistant ground. In the latter case, each mark from the burin scratches through the ground, revealing the plate material beneath (typically copper). The plate is then submerged into an acid that etches into the exposed lines, deepening them (this process results in an “etching”). Areas still covered by the acid-resistant ground are unaffected. Once the plate is ready to be inked, the printer smears it with ink, taking care to force it down into the incised lines. The surface of the plate is then wiped clean, leaving ink only in the lines. The plate is printed with the aid of a press which uses high pressure to force the fibers of the paper down into the incised lines, where they pick up the deposited ink.

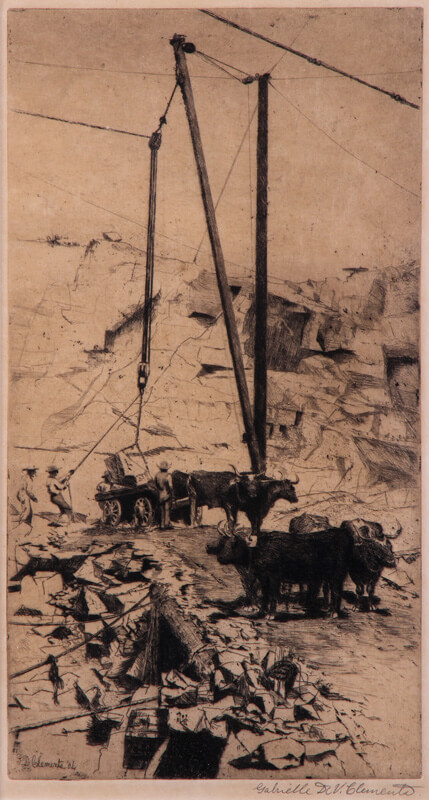

Gabrielle de Veaux Clements (1858-1948), The Derrick (Rockport Quarry), 1884. Etching on paper. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Gift of Harold and Betty Bell, 1999 [acc. # 1999.37].

A printer can create a range of atmospheric effects by varying the amount of ink wiped away prior to printing. In the etching pictured here, we can clearly see the shape of the plate against the raw tone of the paper on the border. Gabrielle de Veaux Clements left a thin film of ink on the plate surface, particularly in the upper part of the sky, where the value is slightly darker than the paper tone. To achieve the darkest tones in the image (the oxen), Clements employed a technique called hatching, which is done by scratching many lines together in tight proximity. ■

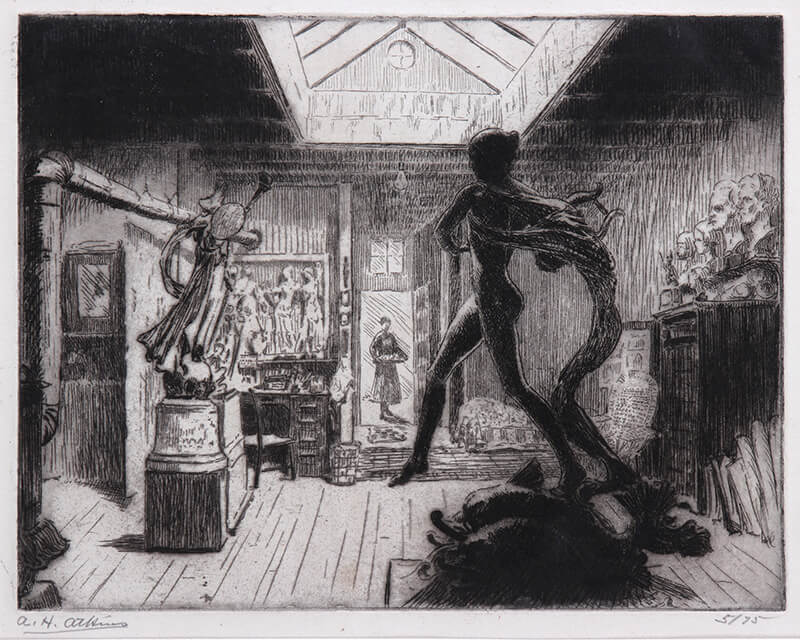

Albert H. Atkins (1899-1951), Under the Skylight, early 20th century. Etching on paper. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Gift of Mr. C. Malcom Watkins, 1983 [acc. #2387.14]. Albert Atkins also worked in the intaglio process.

Planographic Printing

Planographic printing also uses a block or plate, though here the surface is left perfectly flat. One of the most common planographic techniques is lithography. Historically, lithographers used slabs of limestone, though today metal plates are a common substitute. Instead of carving or incising the surface to vary the transfer of ink, lithography exploits the principle that oil and water don’t mix. First, the artist uses a special oily crayon to draw a design on the porous stone, and then the surface is prepared in such a way that the un-drawn areas absorb water. The stone is then rolled with oil-based ink, which clings to the lines made by the greasy crayon and is repelled by the water-filled areas. When the stone is printed, the ink transfers from the crayon marks onto the paper. The immediacy of the process from drawing to print made lithography a popular medium for many artists, including Fitz Henry Lane, who began working at Pendleton’s Lithography in Boston in 1832 and continued to work with the medium throughout his entire life.

Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), View of the Town of Gloucester, Mass, 1863. Colored lithograph. Pendleton’s Lithography, Boston. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Bequest of E. Hyde Cox, 1998 [acc. # 1998.36.5].

Video still from CAM Video Vault VL57 – Laid Down on Paper: Printmaking in America, 1800 to 1865, 10/28/2017. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA.

In 2017-2018, the Cape Ann Museum held the exhibition Drawn from Nature and on Stone: The Lithographs of Fitz Henry Lane and hosted the symposium Laid Down on Paper: Printmaking in America, 1800 to 1865.

Discover the lithographic insights of visiting scholars and take a deeper dive into the early years of this medium in America by viewing these three recordings of the Lane Symposium from the CAM Video Vault:

Lane Lithographs: An Overview with John Wilmerding

2017 Lane Symposium, Morning Session

2017 Lane Symposium, Afternoon Session

Explore the world of lithography in which Fitz Henry Lane worked and view the artist’s prints at Fitz Henry Lane Online.

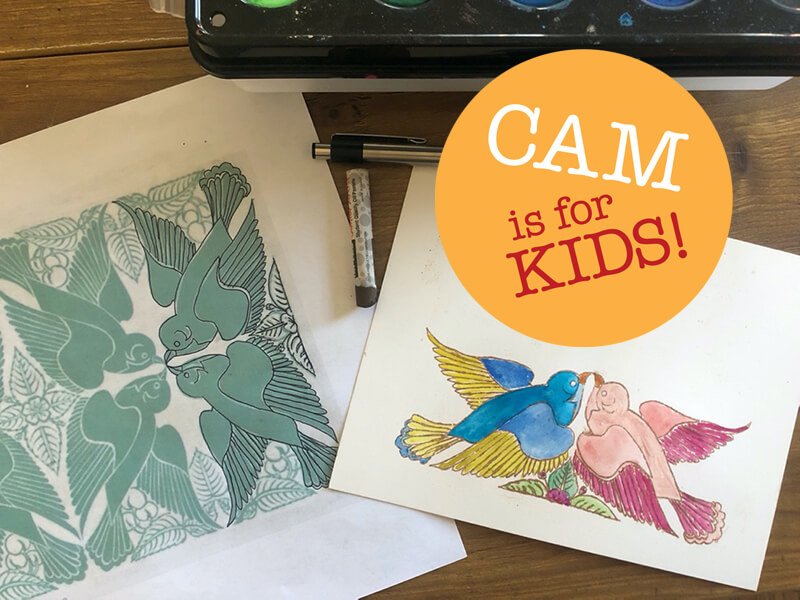

CAM Kids: Monotype

Monotype is another planographic process achieved by painting with ink on a flat plate and then pressing it to a paper substrate to transfer the image. As the name implies, the resulting print can only be made in a single print or edition, as most of the ink is pulled from the plate during the process. Trace monotype is another variation in which an artist inks a plate, covers it with a piece of paper, and then draws a design into the backside of the paper. The pressure of the drawing implement causes ink to transfer onto the front of the paper wherever there is a drawn line on the back.

To learn more about this form of printmaking, and to try it yourself, head over to the CAMKids page and view a lesson plan on how to make a trace monotype using examples of a relief print from the Folly Cove Designers collection.

Unsubscribe | Forward | View in browser

CAPE ANN MUSEUM

27 Pleasant Street, Gloucester, MA 01930

Cape Ann is one of the most important places in the history of American art and industry.

The Cape Ann Museum, thanks to supporters like you, celebrates the history and remarkable contributions of this place to the cultural enhancement of our community and the world at large - yesterday, today and tomorro