October 22, 2021

October 22, 2021

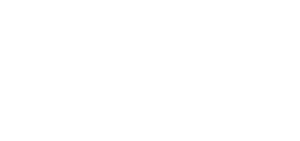

The Giant Ghostly Sheep at Clark’s Farm, October 12, 1914. Photograph by Eben Parsons. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Gift of Ruth I. Parsons and Joseph E. Garland [Acc. # 2357].

Dear Friends,

With the changing of seasons, we are excited to bring to you this 30th edition of CAM Connects!

Introduced to audiences 18 months ago at the beginning of the pandemic, the CAM Connects series has brought fascinating insights into Cape Ann as a unique and inspiring place. This current issue of CAM Connects does not disappoint and, supplementing the superb contributions of the Museum’s dedicated staff, this edition includes articles by a Museum Docent and a CAM Board member, as well as other members of this community. The collective participation and engagement between CAM staff and volunteers underscores one of the many strengths of this wonderful institution, and enhances the Museum’s ability to share and celebrate the role that Cape Ann has played in changing the course of American art and history.

In the coming weeks members will also be receiving in the mail a printed edition of the CAM Report looking back at 2020 and 2021 to explore how the Museum has responded to the challenges of COVID – “thinking outside the gallery” and engaging the community in new, meaningful and creative ways.

This is a time of great momentum and dynamism for the Museum. Please do visit over 650 community portraits on view in Quilted Together: An Exhibit of Community Portraits at the Janet and William Ellery James Center through November 5. We look forward to seeing you at the Museum on Pleasant Street as well, where we have a new Sea Serpent on view in the recently reopened CAM Studio, and where starting on October 30 visitors will be able to enjoy a new temporary exhibition, Cape Ann & Monhegan Island Vistas: Contrasted New England Art Colonies.

Oliver Barker, Director

Folklore, Legends, & Myths

Fall is in the air and with it the folklore, legends, and myths from across Cape Ann swirl to life as residents settle in for darker evenings around wood stoves and heaters. The stories shared over campfires tell histories that are inextricable from the ones captured in our collections and archives, no more or less valid because of their roots in oral tradition rather than written record. From different artistic interpretations of mythic serpents to tales from Bearskin Neck and Dogtown; from ghostly portraits to near misses on the ships, the examples in this issue of CAM Connects highlight the inherent connection between the romantic and the historic. Wherever people gather, they tell stories of how they got there, what there is to be careful of, and what there is to be grateful for. ■

A Tale of Three Serpents

The imagination is a powerful creative force, one that blurs that thin and moving line between history and myth. After all, what is mythology if not imaginative history? Tales of great floods, primeval heroes and mythical beasts excite our imaginations as much today as ever. Generations of artists have drawn from these wells to bring these myths to life. Some, like the great serpent, resonate so deeply with our imaginations that they’ve become archetypes, appearing in creative works across cultures and eras.

Midgard Serpent, James T. McClellan, c. 1967. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Gift of the artist, 2000 [Acc. #2000.33.05].

A comparison of two works in the Cape Ann Museum’s collection offers a window into this world of imagination. James McClellan’s c.1967 sculpture Midgard Serpent depicts the great sea monster said by Norse myth to encircle the world, and provides a unique counterpoint to Goon Chan’s c.1920s work Dragon which depicts a serpentine three-clawed dragon drawn from Chinese myth, gliding through ribbons of smoke. Though each piece is distinctive compositionally, the two works share many similarities. They are both carved reliefs, made of largely unpainted wood with small flourishes in gold leaf or red and black paint. Each also brings to life a mythic serpent, albeit with different cultural roots.

Dragon, Goon T. Chan, c. 1920s, wood, paint. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Gift of Harold S. Maddix and R. Betty Archer, 2012 [Acc. #2012.136].

That both artists spent time here on Cape Ann invites us to consider the role of a third serpent in linking the two works: the Cape Ann Sea Serpent. Were McClellan and Chan familiar with this local legend? McClellan is known to have embraced mythic imagery in his work, having regularly sculpted griffons, phoenixes, trolls and mermaids. “Mythology should not be neglected,” he once proclaimed. In contrast, little is known about Chan’s interest in myth. He is best remembered as a portraitist, and so his dragon may be more unique amongst his body of work. What was it that moved these two artists to breathe life into these twin mythical monsters? Could our local sea serpent have fired the creativity of either sculptor? Fittingly, the answer is left up to our imaginations.

Stop by the CAM Studio to see the Cape Ann Museum’s newest serpentine artwork, a mural of Cassie the Sea Serpent by Grimdrops. Listen to Cassie’s tale during a family talk with M.T. Anderson, author of The Serpent Came to Gloucester, on Saturday, October 30. ■

The Legend of the Bear

By Paul St. Germain

The oldest known record of how Rockport’s Bearskin Neck received its name has been a question mark for many years. In Eleanor Parsons' book Bearskin Neck, she related that the name goes back at least 300 years. By 1700, much of the dense hemlock forest surrounding all of Cape Ann had been harvested and used for the wharfs in Boston and other ports, which allowed the bears and other wild animals to roam freely right down to the ocean front. As they became more of a nuisance, bears especially were singled out by the men of the area to be hunted. The most common version of the Babson-killing-the-bear story was told by young 10-year-old Henry Witham, who recounted how his “Uncle Babson” confronted a bear on the Neck and slaughtered the animal with a fourteen-inch knife. He then skinned it and laid out the pelt to dry on the rocks. ■

Mystery, Mayhem, and Magic in an Abandoned Cape

Ann Village

There lie the

lonely commons of the dead—

The houseless homes of Dogtown. Still their souls

Tenant the bleak door stones and cellar holes

Where once their quick loins bred.

-Percy MacKaye: Dogtown Common

By Suellen Wedmore, CAM Docent

Who can resist a story about a “witch” who hexes an ox so that it “freezes in place, its tongue dangling from its mouth?” There is something enthralling about vivid tales from our past, whether they are factual or embroidered upon, and the tales from our own Cape Ann Dogtown are rich with mystery, magic, and drama. Stories of the colorful people who once lived there were widely shared and have become part of the literature of our era.

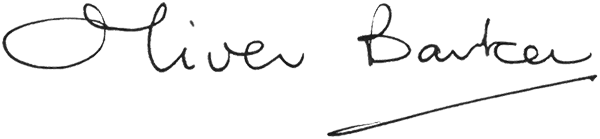

(left) Cape Ann Scenery, John S. E. Rogers, No. 71 Teaming Stone. "A quarry scene at Rockport, showing a team of oxen hauling a large piece of stone upon a carriage" 1870.

(right) Below Fox Hill, Alewife Brook, c. 1895. Photograph by Dr. Gilbert Norris Jones. Gift of Margaret Little Dice, 2001 [Acc. #2001.61]. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA.

One of the most colorful of these characters was Fox Hill townswoman Luce George, whose ability to put a spell on anyone who dared cross the Alewife Brook Bridge below her Dogtown home was well known, and who was, consequently, almost always successful in coaxing tribute from an oxcart’s cargo—a mackerel, perhaps, a few ears of corn, or a bundle of wood for her fireplace.

Following in Luce’s footsteps was her legendary niece, Thomazine “Tammy” Younger, who fell heir to both her aunt’s dilapidated house and her reputation. Upon hearing hooves on the bridge below her, she would fling open a window and fill the air with obscenities until a toll would be offered. ■

Very Superstitious - Goode's Writing on the Haul

Mackerel sky and mares’ tails,

Make lofty ships carry low sails.

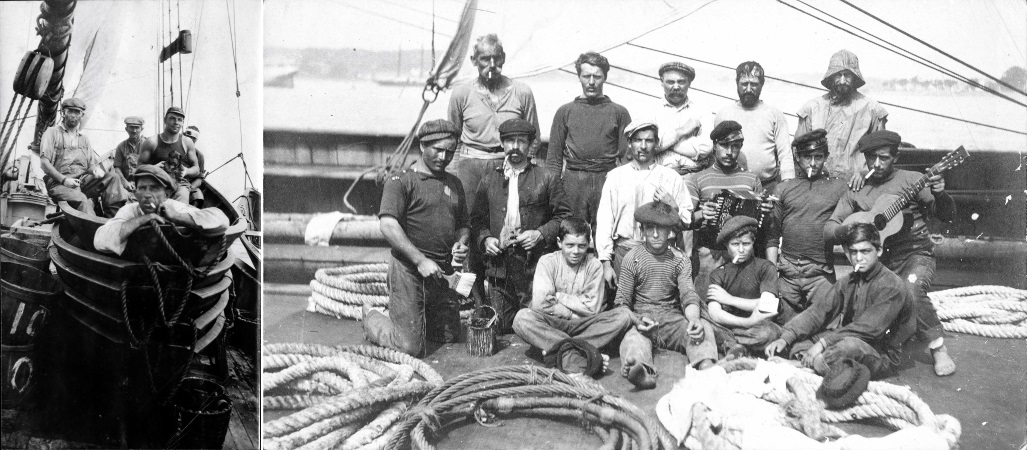

(left) "Bronchos of the sea and their riders," c, 1920s. Gift of Gardner Lamson, 1995 [Acc. #1995.54].

(right) Crew of an Italian Salt Barque, c. 1910. Photograph by Chester N. Walen. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA.

While stories abound about how superstitious fishermen and seamen are and have been over time, they are probably no more so than any other group of individuals. Writing in the 1880s, George Brown Goode (1851-1896), an ichthyologist and employee of the Smithsonian Institution, came to this conclusion after digging deep into superstitions held by Gloucester fishermen. Despite this summation, however, Goode could not resist recounting many of the superstitions held by fishermen of this port in his monumental work The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States, published in 1887. Here is an abbreviated list of what Goode observed.

- Often fishermen were labeled as Jonahs and discharged from their posts, even though no fault could be found in their work. One way it was determined if someone was a Jonah was for the ship’s cook to put a nail or a piece of wood into a loaf of bread he was baking. The unlucky fisherman who discovered it on his plate was declared a Jonah.

- It was considered bad luck to kill a petrel, often referred to as a “Mother Carey’s chicken.” Goode found that this superstition was dying out by the 1880s as fishermen were often obliged to kill the birds for bait.

- Some fishermen refused to have their hair cut when the moon was waxing, fearing that if they did all of their hair would fall out.

- It was commonly thought that nailing a horseshoe to the bowsprit of a fishing schooner would bring the vessel good luck.

- To leave a hatch cover bottom side up on the deck of vessels was considered unlucky and to have a hatch cover fall into the hold was considered an especially bad omen.

To learn more about the superstitions of Gloucester fishermen in the past, spend some time in the CAM Library & Archives perusing George Brown Goode’s The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States. ■

The Record of My Ancestry

By Susanna Natti, CAM Board Member

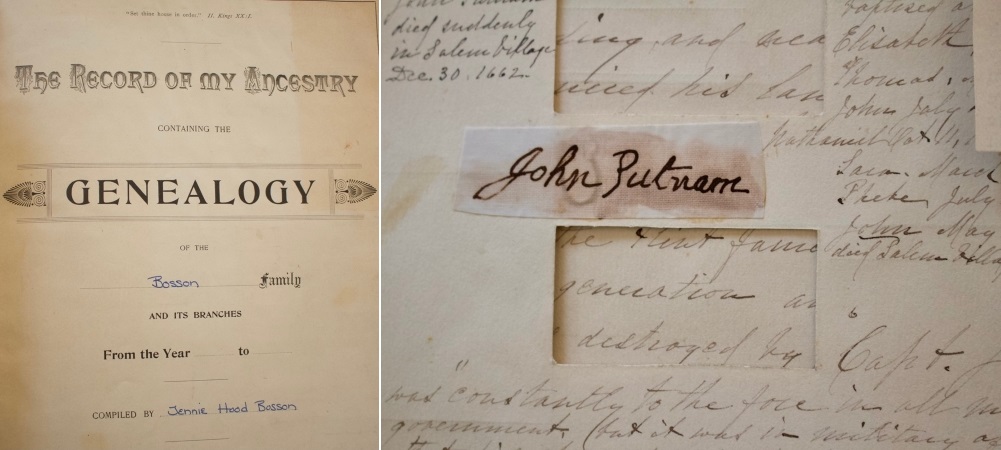

Title page and page containing signature of John Putnam, a signer of the testimonial to Rebecca Nurse from The Record of My Ancestry Containing the Genealogy of the Bosson Family, 1892. Private Collection.

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise, considering how many of my mother’s family arrived before 1700 and how many of them lived in Salem, that the Salem witch trials are part of my family history. After I found the ninth ancestor who was involved in that horrific time in my Great-great-aunt Jennie’s genealogy, I was struck, not by the fact that long-ago family members were caught up in it, but that they represented the full spectrum of the story, from the accused and their defenders to those indicting and jailing the accused.

Jennie Hood Bosson (1850-1936) from pages of The Record of My Ancestry Containing the Genealogy of the Bosson Family, 1892. Private Collection.

Three sisters of a direct ancestor from a Topsfield family were accused; two were hung. One of them was Rebecca Nurse. Four ancestors in Aunt Jennie’s genealogy were among those who signed a testimonial to Rebecca Nurse’s good character. How desperate they must have felt to see this incredible and impossible scenario unfolding and to be so powerless to stop it. One of those signers was just sixteen. I try to imagine what that was like for her. ■

Portuguese Crowning Ceremony

Crown (modeled after 1902 crown used during Our Lady of Good Voyage Church’s annual Crowning Ceremony. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Gift of David A. Rose, 2015 [Acc. #2015.030.1].

The crowning ceremony which is celebrated annually in Gloucester’s Azorean community originated in a 14th century legend about Queen Isabella of Portugal. Devoutly religious and charitable, she smuggled bread in her apron to the poor against her husband’s wishes. When the king asked her what she hid in her apron, she said roses. Assuming she was not telling the truth, he tore open the apron. Miraculously, roses fell from it and a white dove appeared. In gratitude for the miracle, the queen began the tradition of crowning one of her subjects imperator, or king, for a day.

Today, an annual Festival of the Crowning is celebrated at Our Lady of Good Voyage Church, the church of Gloucester’s Portuguese community. The local ceremony was started by Captain Joseph P. Mesquita (1859-1933), a native of the Azores and one of Gloucester’s best known fishing captains. In 1900, Mesquita and all but one member of his crew escaped death when his schooner Mary P. Mesquita was run down by a steamer on George’s Bank. Following their rescue, Mesquita met with the pastor of Our Lady of Good Voyage and arranged to have a silver crown made in Portugal in gratitude for their safe return. The crown was blessed by Pope Leo XIII and has been used in every ceremony since 1902. A small silver replica of that crown is often on display at the Cape Ann Museum. ■

For more information on the Crowning Ceremony, click here.

Ghostly Miniature

Unattributed artist, Benjamin Somes (1786-1813),” c. 1810, oil on ivory, metal, glass (braided hair enclosed in locket). Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA.

This “ghostly miniature” in the Museum’s collection is a portrait of Benjamin Somes (1786-1813) whose story is told by his great nephew, past Museum president and curator Alfred Mansfield Brooks (1870-1963), in his book Gloucester Recollected. You can also read about the legend in the book Ghost Stories of New England by Susan Smitten found in the CAM Library & Archives.

Benjamin Somes was engaged to Eliza Gilbert and eager to marry immediately. However, the couples’ parents insisted that they wait until Benjamin returned from a trip to China for trade. He made his voyage safely but came back to a stormy morning in Boston—the weather so severe that he could not take the usual horse-drawn coach to Gloucester. Despite the conditions, he rented a horse and rode through the worsening storm to return to his Eliza. There were jokes from Eliza’s waiting family about his love “being too blind to recognize a puddle if he fell in one, but also too hot to be cooled off by it if he should.”

At ten o’clock before bed, Eliza unclasped her lover’s miniature that she wore as a locket around her neck. Before her eyes, the color of the portrait’s cheeks paled to the color of a ghost, and she fainted at this supernatural vision that he was dying. The next morning, she received news that Benjamin and his horse had been found dead at the Cut Bridge in Gloucester, just a mile away from his love. ■

Unsubscribe | Forward | View in browser

CAPE ANN MUSEUM

27 Pleasant Street, Gloucester, MA 01930

CAPE ANN MUSEUM GREEN

13 Poplar Street, Gloucester, MA 01930

Cape Ann is one of the most important places in the history of American art and industry.

The Cape Ann Museum, thanks to supporters like you, celebrates the history and remarkable contributions of this place to the cultural enhancement of our community and the world at large - yesterday, today and tomorro