July 27, 2023

Dear Readers,

As promised last week, today’s Letter is all about the talk of the movie-town: Barbie and Oppenheimer. By now your ears might be ringing with takes on the two movies, but in our lead review, scholar and critic Nathan Lee cuts through the noise with his incisive reading of Greta Gerwig’s bubblegum blockbuster as something smarter than girlboss fantasy or canny corporate sellout: a grappling, rather, with the fundamental ways in which we represent and relate to reality.

For more on these themes, read Devika’s fascinating interview with Gerwig about Barbie, which touches upon a range of references, including Shakespeare, The Truman Show, Noah Baumbach’s White Noise, Wes Anderson’s sets, John Cassavetes’s Husbands, and more.

On the podcast, we turn to Oppenheimer, with guests Madeline Whittle and Mark Asch. Christopher Nolan’s epic about the “father of the atomic bomb” generated wildly diverging reactions among the group, and the result is a lively debate about everything from Nolan’s representation of history to his techno-fetishistic flourishes to the film’s portrayal of Albert Einstein.

Finally—don’t forget to fill out our two-minute Film Comment readers’ survey below, if you haven’t already! The deadline is August 1. By submitting, you’ll be automatically entered in a raffle to win a poster of Werckmeister Harmonies signed by Béla Tarr.

As always, thank you for reading and listening.

Yours sincerely,

Devika Girish & Clinton Krute

Co-Deputy Editors, Film Comment

Making Contact

Help us get to know you better by taking this brief, two-minute survey. Participants will be automatically entered to win a Werckmeister Harmonies movie poster, autographed by legendary director Béla Tarr.

The deadline is August 1, 2023, so be sure to fill out the survey soon to be eligible for the drawing. This giveaway is restricted to U.S. residents. If you’ve already submitted a survey, a heartfelt thanks. And if not, we hope to hear from you soon!

Barbie (Greta Gerwig, 2023)

Plastic Fantastic

By Nathan Lee

By the time you read these words, the detonation of Barbie discourse will likely have faded to its most tedious aftereffect: commentary on the mountain of gold it accumulated on opening weekend and What This Means for the Movies (and for Women). You have surely endured, and perhaps contributed to, one of the half-dozen meme cycles the film has engendered since it broke the internet. You will have followed the factions of the Barbie vs. Oppenheimer contretemps as they reached the cringe détente known as Barbenheimer. Now that every corner of the cultural commentariat has weighed in, you may have read that Barbie is an exuberant girlboss fantasia, that it is yasss and slay, that it has its cake and eats it too. Alternatively, you may have been informed that just as there is no ethical consumption under capitalism, there is no feminist anti-capitalist critique immanent to a cinematic production beholden to Mattel, Inc. Alas, you might even have heard the bobbleheads on Fox News denounce the film as “anti-man” and accuse it of promoting “trans grooming,” a phrase that can only be taken seriously when applied to transgender employees at a dog spa.

Perhaps you have opinions on Greta Gerwig leaving Indiewood behind to go full Hollywood, and have judged her a sellout, or hailed her as Powerful Woman Who Can Do What She Wants. Or perhaps you simply find yourself grateful that it was she who thus declared her career ambitions rather than her partner and co-writer Noah Baumbach—who, of the two halves of this cinematic power couple, is decidedly not the one you would wish to see direct a Thor movie. You may have read an article in The New Yorker detailing Mattel’s plans to launch an entire slate of movies based on their trinkets and cursed your existence in our world, the worst of all possible multiverses.

After a screening of Barbie in Manhattan, an attendee sharing an elevator with the legendary critic Amy Taubin asked if she was “inspired” by the film, to which she retorted, “It’s about a fucking doll.” Barbie is indeed a movie about a fucking doll, and if we posit that it is stupid to make a movie about PVC thingamajigs, it seems only fair to counter that Gerwig is not a stupid filmmaker. Once we accept the fact that Barbie is about a fucking doll, we must then come to terms with how it is a movie about a fucking doll. Gerwig has given this problem considerable thought, and if, like the oversized discourse it provoked, Barbie is a text of maximalist contradictions, that may well have been the best possible outcome. It does not seem unwarranted, in a movie that references Proust, Marx, and Zack Snyder’s Justice League (2021), to cite a remark by the philosopher Gilles Deleuze: “cinema is always as perfect as it can be, taking into account the images and signs which it invents and which it has at its disposal at a given moment.” That our moment is dominated by world-devouring corporate IP is at once the subject, object, and symptom that Gerwig confronts in her madcap extravaganza of commodity auteurism.

The plot is blatantly metaphysical. Afloat in bubblegum-pink Barbieland, where a vibrant array of diverse Barbies rule the world and Ken is just… Ken, our plastic protagonist, Stereotypical Barbie (Margot Robbie), brings her metaverse to a screeching halt by asking her fellow Barbies if they ever think about death. This glitch in the Mattel Matrix is prompted by the sad feels of whoever in the real world is playing with Stereotypical Barbie. As explained by Weird Barbie (Kate McKinnon)—a doll who was played with “too hard,” and now has spiky hair and ultra-flexible limbs—the only way to restore order is for Barbie to make the journey to the mirror realm of Los Angeles, locate her puppetmaster, and restore cheerful, smooth-brained vibes.

Gerwig is shrewd enough to reject a facile dichotomy between the imaginary and the real worlds from which her characters, human and otherwise, pass back and forth. The “real” Los Angeles on display feels no less artificial than Barbieland, and if that comes with predictable jokes about the phoniness of Hollywood, the more striking consequence for the viewer is to be placed in a position from which, narratively speaking, there is no reality at stake. Which is to say that Barbie is less convincing as a pop feminist manifesto than as a treatise on representation. In one sense of this term, the movie deals in problems of moral representation. The film’s racial and physical spectrum of Barbies would satisfy the Chief Diversity Officer of Mattel, even as it insistently lampoons the harmful effects of the doll on women’s self-image. But to take the gendered politics of the movie seriously—indeed, to locate any coherent politics at work—is to miss another, richer question of representation at the level of form and aesthetics that the movie explores.

Barbie is singularly engaged with the fact that cinema consists of images in relation to each other and nothing else; whatever links we forge between a movie and our lived reality or history are entirely phantasmic. This may seem obvious to the point of banality, but the phenomenon by which we invest cinema with our beliefs, values, identifications, and desires is a deeply mysterious process that film theory—notably feminist film theory—has grappled with since its inception. Cinema is the ideological cultural form par excellence because it so vividly embodies the definition of ideology proffered by the Marxist theorist Louis Althusser: ideology is the image we maintain of our relation to the real world. Barbie is a sustained enactment of ideological logic in this sense. The entire movie is a blitz of images that survey various relations we presume to maintain with the world while effectively leaving “reality” out of the picture.

Many of the film’s best jokes exemplify this idea. Having tagged along with Stereotypical Barbie on her voyage to Los Angeles, where she is flustered to encounter the novel phenomenon of misogyny, the film’s primary Ken (Ryan Gosling) wanders off and discovers the even more astonishing notion of “patriarchy.” His inauguration into the reality of male power is hilariously evoked in a psychic montage of American presidents, CrossFit himbos, and macho cultural iconography—most seductively, in his thermoplastic cortex, men on horses, lots and lots of horses. Returning to Barbieland thus reprogrammed, Ken proceeds to give his reality a cartoonish überdude makeover. Confronting a motherland suddenly run amok with Kenergy, the Barbies plot to undermine the new paradigm by exploiting the fact that “Ken contains the seeds of his own destruction.”

Hence one Barbie bamboozles her Ken by feigning ignorance of how money works, others ask for help in understanding how to do sports, and another—in a pièce de résistance squarely aimed at the kind of film bro who thinks Christopher Nolan is a genius—hoodwinks a Movie Ken by faking ignorance of The Godfather (1972) so he can mansplain cinema. Throughout these scenes and dozens of others, Barbie perpetually foregrounds its groundlessness. The movie is pure simulacrum—a copy with no model. Its true sisterhood is the company of films like Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle (2003), Southland Tales (2006), and Speed Racer (2008), whose ruling principles are flamboyant pastiche and self-devouring reflexivity.

Curiously enough, this is where Barbie does exert a political effect. Chief among the objects dissolved in its postmodern exuberance is the idea of “woman” itself. To whatever extent Barbie is read as empowering or cynical, a satire or a sellout, the text of the film insists on the constructed nature of its fantasy and throws into doubt any correlation to the real world we might hazard. And that’s the barb that Barbie hangs us on. In a world that is patriarchal, in a movie that does exist to glorify dumb IP, “woman” can only be a mirage and a question to be posed. The triumph of Barbie is to affirm that we are all plastic fantastic, and no one gets to determine what being a woman means—not Greta Gerwig, not Mattel, and certainly not a fucking doll.

Nathan Lee is an assistant professor of film at Hollins University and a longtime contributor to Film Comment.

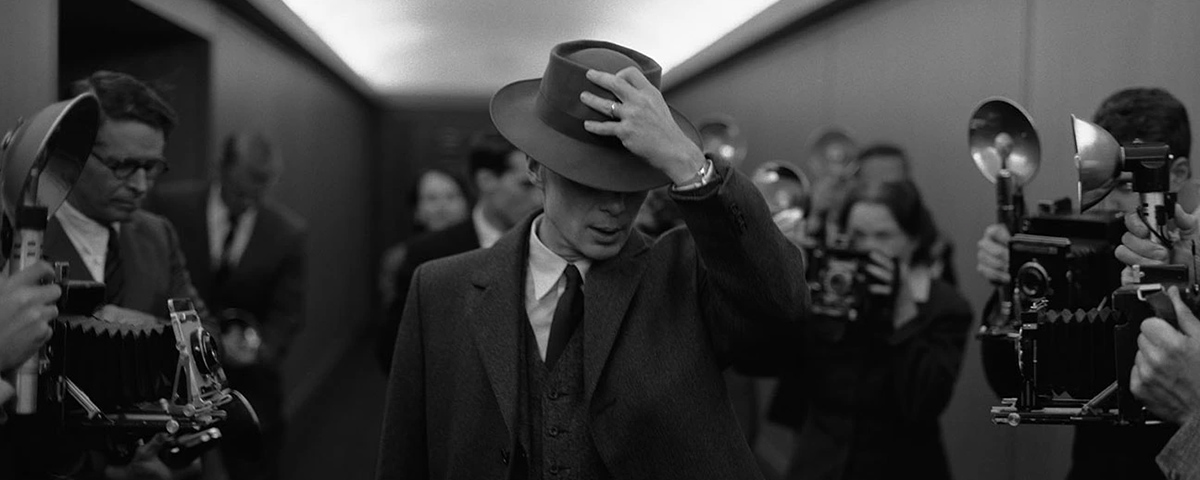

Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster Oppenheimer, a biopic of J. Robert Oppenheimer, one of the key leaders of the Manhattan Project, has sold out movie theaters all over the country. With its three-hour runtime, notoriously large 70mm IMAX reels, and star-stuffed cast, it is nothing less than an epic. The film spans nearly four decades, from Oppenheimer’s stint as a physics student in Europe, to his time teaching at UC Berkeley during World War II, to his days developing the atomic bomb at the Los Alamos Laboratory, and, subsequently, to the investigation into his possible communist ties during the McCarthy era. Amid all that plot is plenty of awe-inspiring spectacle and musings on the ethics of war and the perils of genius.

On today’s episode, Film Comment Co-Deputy Editors Devika Girish and Clinton Krute are joined by Film at Lincoln Center programmer Madeline Whittle and critic Mark Asch for a discussion about Nolan’s opus. The group was evenly split between fans and skeptics, and the result was a lively conversation—which, of course, is what the movies are all about.

Photo by Jaap Buitendijk © 2023 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Interview: Greta Gerwig on Barbie

By Devika Girish

Amid all of the discourse rustled up by Greta Gerwig’s Barbie—from pessimism about Mattel’s unabashed deployment of indie-film talent in service of product placement to both joy and exasperation at the film’s sparkly-pink, nudge-nudge/wink-wink representations of feminism and masculinity—one thing has seemed clear: that Gerwig is a director with a vision. Barbie is a beautifully crafted and exuberantly silly movie rife with the contradictions and inversions of a truly postmodern work. Last week, I caught up with Gerwig over the phone about writing the film with Noah Baumbach during the pandemic, seeking advice from Peter Weir, imbuing inanimate objects with feeling, and balancing cynicism and care.

I watched Barbie and thought: why does this remind me of White Noise? I wondered if it was the pop colors, the fact that both movies are a little camp… and then I realized, it’s the fear of death! That’s the kernel of both films. You and Noah worked on them at roughly the same time—did you sense that parallel, too?

It’s funny, you’re the very first person to pick up on that, though it feels extremely obvious to Noah and I. Both movies were born out of this surreal moment of being in lockdown in the midst of this global pandemic. I remember both of us being on separate Zooms. He’s working with his designers, and I’m working with my designers. We’re building these worlds simultaneously. And the thing we loved most—going to movie theaters, sitting with people, watching something and being transported—was not available at all to us at that time. I don’t want to speak for Noah insofar as White Noise is concerned, but Barbie came out of this overwhelming sense of, “Well, if they ever let us back, if we ever get to do this again, if there are even movies on the other side of this, let’s do something wild and anarchic and unhinged and joyful and filled with fear” [laughs]. I think we both desperately wanted to experience movies with people again.

The movie pits women against men, the Barbies versus the Kens. It made me wonder about the writing relationship between you and Noah. What distinct sensibilities did each of you bring to Barbie?

I think there was something extremely delicious in that conceit that we’d set out where everything is reversed and then reversed and then reversed again, so that actually locating what Barbie means, what Ken means, and how that grafts onto the world is very complicated in absurd turnings. That reminded me of when I saw Mark Rylance perform with his all-male Shakespeare troupe. He did Twelfth Night followed by Richard III, and they were the most wonderful two nights of theater I’ve ever experienced. It was extraordinary, especially because when Shakespeare was originally performed, it was all men doing it. It’s men dressing as women dressing as men dressing as women... You start getting so far from what feels “normal” that you feel lost in the heightened-ness of reality. I felt like what we were able to do with all of the turnings in Barbie was locate our identities as creators in really unsuspected places. It was made together in a gleeful whirligig where there wasn’t some sense of “He’s the Ken and I’m the Barbie.” I’m just as much the Kens as the Barbies, and we’re both Gloria, and my mom is Sasha, but I’m also Sasha. It had enough complication that what emerged was something much wilder than any sort of direct correlation.

It’s very postmodern—we’re all Barbies, and we’re also all Kens. We can fill these toys with whatever we want. I read in the press notes that you called Peter Weir, who directed The Truman Show, to ask about achieving that balance of emotion and artifice. What did he say to you?

He was so generous to get on the phone with me. He’s an incredibly lovely man in addition to being a great director whose movies span all different kinds of genres and tones but always stay human. We talked a lot about the execution, because I was still in the stage of figuring out how I wanted to realize this world from a practical standpoint. I knew I wanted Barbieland to be reminiscent of ’50s soundstage musicals, in part because Barbie was invented in 1959, so to ground [the film] in that interior-soundstage world of Vincente Minnelli musicals, Gene Kelly, Oklahoma!—where there’s an artifice that almost becomes more real in its fakeness—felt correct to me. But the largest stage in the U.K. is I think Cardington, and you need a lot of soundstages to execute something like that, and they have their own limitations. Because as big as they are, they’re only ever in a box.

That’s a nifty catchphrase for the movie!

Exactly, the box was part of it—it mirrored everything we were trying to do. What I was interested in talking to Peter Weir about was how there are moments in The Truman Show that clearly were shot on a soundstage—like the boat running into the wall, which is so outrageously beautiful, but it’s obviously an interior made to look like an exterior. But then there are other moments, like outside of the house with all the cars, where I thought: that’s too big, that’s not on a stage—but it feels like there’s stage lighting. The quality of sunlight is different from the quality of stage lighting, and those scenes felt molded by light. And he told me he did shoot a bunch of those sequences outside, but he set up stage lighting.

They were in Florida in the heat, and the lighting made it even hotter, so he said I probably didn’t want to do that—“That’s going to be a bit of a nightmare.” But the nuts and bolts of how he did it were the main content of the conversation. Anytime you’re on the phone with Peter Weir, try to get him to talk about how he made stuff.

Speaking of stuff, there’s so much of it in this movie. The press notes are full of details about the cars, the backdrops, and every little outfit, which were all painstakingly created. Your movies have tended to be very character-driven. What was it like to work with so many objects on this one?

I thought about that a lot while making the movie, and there are many other filmmakers you can use as an example for this, but the one that sprung to my mind was Wes Anderson and his constructed worlds. For him the objects are emotional, and the sets are emotional. There are the emotions of the characters, and then there are the emotions of the inanimate objects. That was something I wanted to tap into. Kids have tremendous amounts of feelings about inanimate objects. I can’t tell you how many kinds of little cars and vehicles my son has, and if he’s missing one, he’s like, “Where did my grabber go?” And I’m like, “You have so many, what do you mean?” And he’s like, “I know I put it there, and I was going to do this and this with it.” He has this whole narrative, and I realized, this is his emotional landscape. And so, insofar as Barbie is about dolls, which is a thing of childhood, it had to have that emotion in the physicality.

That’s what was so gorgeous about being able to make a movie like this. Sarah Greenwood was leading the production-design team, and we got to build these large-scale sets, these beautiful painted skies. Rodrigo Prieto the cinematographer and I got to look at photographs of something like 20 permutations of painted skies and blues with different clouds to see how they reacted to different photography. I mean, we took so much time with just the blue of the sky, and how it reacted if we lit it from below, because we wanted to do that old-film technique of making it look like twilight through lights hidden behind mountains, that kind of thing. We also had a miniatures department, which was building small versions of things that were large, and then expanding the world so we could photograph it and use it like they did in 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars, where you’re compositing the image with miniatures. I find miniatures to be very filled with emotion, because they’re beautiful, but it’s also the labor that’s put into them. I remember the day I saw these incredible palm trees they had built, with painted fronds, and then I saw them on the miniature set, and they were identical. It made me emotional, the care and also the tactile nature of it, which felt like an extraordinary opportunity for a kind of filmmaking that there are not many occasions for.

In Lady Bird, a character says, “Don’t you think maybe they are the same thing? Love and attention?” I remember you saying that line was inspired by Simone de Beauvoir. I was thinking about that while watching Barbie, and the act of critiquing and loving something at the same time. This film is trying to have its cake and eat it too, in a sense. There’s a scene where Gloria (America Ferrera) pitches a more realistic, sort of depressed Barbie to Will Ferrell’s Mattel CEO, and he says no. But then someone on his team crunches numbers and tells him it’s going to make money, and he immediately changes his tune. That scene undercuts the whole film, while still keeping the fantasy alive. It made me think about this ability of yours to be cynical while also recognizing that cynicism is a product of care.

Cynicism as a product of care… that’s so interesting. Gosh, I don’t know, that’s beautifully put. I mean, yes. To double down on the box metaphor, this film is looking at the constraints of the box, and then there’s me, the filmmaker, standing and looking at the box. But also, the film has to acknowledge that me looking at the box is inside of another box. To go back to the idea of the flipped and the re-flipped and the flipped again—these layers of inversion, with meaning becoming absurd, are only possible in something that’s already doing that at its core. It’s certainly not solving for it. It doesn’t answer it. I always think of Husbands, that great John Cassavetes movie. There’s a moment at the end where Ben Gazzara is gone, and the characters [played by Cassavetes and Peter Falk] have been drinking all night and are talking in front of this driveway, and the boom drops into the shot. Cassavetes kept that in the movie, and it’s great. It does not take you out of the raw emotion, the grief, that these men are feeling. You’re still with them, even though you’re in on the constructedness. That was also part of wanting to be in a staged musical world and drawing attention to it. I don’t have an escape plan to get out of the bigger box. But it felt important to keep turning it back on itself. And the truth is: it could keep going ad infinitum if you wanted it to, but it seemed that by acknowledging these layers of irony and cynicism, you end up with something that feels like sincerity.

Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (Todd Haynes, 1988)

- The release of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie has thrust one of the great independent films of the ’80s back into the zeitgeist: Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1988) by Todd Haynes. The 43-minute film uses Barbie dolls to represent the titular singer—who died in 1983 of complications arising from anorexia nervosa—and the various figures in her life, and was famously blocked from theatrical release for using copyrighted music without permission. Read Michael Koresky on the film, which even now is viewable only in bootleg form: “Superstar, by design, is not something you fondly recall; like Safe, it’s a film that uses a literal disease as cover for something less medically diagnosable—a social rot so deeply entrenched that there may be no cure.”

- Alain Gomis’s Rewind & Play, an inspired archival reworking of a 1969 French television documentary about jazz composer and pianist Thelonious Monk, screens on August 1 at Nowadays. Read Clinton Krute on the film: “Gomis’s edit is a surgical dissection of the power dynamics between those behind the camera and those in front of it: the film cuts between extreme close-ups of Monk, in Paris to close out a European tour, and the fussing, hectic efforts of the film crew as they follow him through the city.”

- As actors and writers strike for more control over how their work and likenesses are used by studios, Netflix reportedly posted a job opening for a product manager for a machine learning platform with a salary of up to $900K. Read Daniel Witkin’s feature from Film Comment’s September-October 2019 issue on the questions raised by the ability to create AI personas of actors: “If a mercenary corporate entity could replace inconveniently autonomous performers, writers, and directors with pliant and predictable algorithms, why wouldn’t they? As Robert De Niro once mused in an interview, in the future ‘they’ll do a likeness that you have to fight for the right to own.’”

Thank you for subscribing to the Film Comment Letter. The original writing featured in the Letter is available exclusively to subscribers on Thursdays before being published on filmcomment.com the following Monday.

SUPPORT NONPROFIT, INDEPENDENT FILM JOURNALISM. SUPPORT FILM COMMENT.